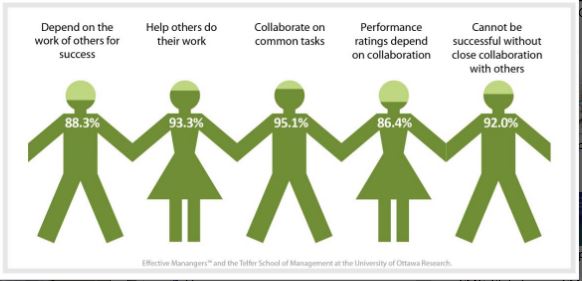

The following figure shows the results of a research project into managerial effectiveness carried out in partnership between Effective Managers™ and the Telfer School of Business at the University of Ottawa. In this part of the research, managers were asked several questions about their interdependence with others.

This same research also shows that organizations with high interdependence have higher role conflict. This higher level of interdependence can lead to situations where managers from one department come into conflict with those in another department. This arises when the tow involved managers do not have the same understanding of how they must work together for mutual success.

Take, for example, the following situation which plays out in most organizations every day.

A manager in Operations is focused completely on an issue within Operations. The Director of the department has called all hands on deck to get that problem solved. Meanwhile, a manager in Finance is accountable to produce a production report which requires obtaining updated information from the manager in Operations. Once can immediately see the conflict… the Finance manager relies on the Operations manager for success. The Operations manager does not see this work as a priority, and probably will not even see it as “real work”, but as a favour.

The opposite happens regularly as well when Operations managers depend on Finance, Human Resources, Purchasing and other departments for success. But how often are the Operations priorities seen as a priority by those other departments?

A larger question is whether these respective managers are resourced appropriately to support each other in these ways. Or are these cross functional duties seen by managers as “good to do if I have time”?

Getting this right starts at the top of the organization.

The CEO’s accountability is twofold. First, it is the job of the CEO, to ensure that work is delegated down the organization, together with scorecards or other measures to track success. But this alone only reinforces silos and works against interdependence unless the respective accountabilities and authorities for work that flows across the organization is also taken into account. So the CEO must also ensure that the right frameworks are in place for delegating work across the organization in an efficient and productive way, so situations of conflict can be avoided.

The right framework helps employees understand how to initiate work with others in different parts of the organization. But it also means identifying specific accountability and authority frameworks between various groups and knowing how to resolve differences as they occur.

For example, with a relatively simple objective to improve delivery processes, multiple departments are involved. The order originates with the sales team. Then it passes to manufacturing who produces the order, before it gets delivered to logistics, distribution and warehousing. IT manages the system. Finance generates the invoice. Finally, the HR department tracks and generates compensation to the original salesperson for making the sale. As you can see, there are multiple departments and levels in the organization that are actively engaged at any one time. Typically the manager in charge of the delivery processes will be accountable for the project, but the requirements for the involvement of all of the other departments are not fully considered. Or if considered, they are done in isolation of the people in those departments that will have to do some of the work.

Organizational systems often break down when there is a single manager named as the individual accountable for a process, such as the one in the example. In most cases, this person does not have the appropriate authority to make decisions to improve or resolve conflict with any part of the process. In our example, the CEO is the one individual in the organization who has the authority to decide and direct. As the single point of accountability, the CEO is in charge of all departments and is the only one who can make decisions on issues involving affecting several departments at once.

Certainly the CEO does not do all of the work alone, and there will always be people below him or her with accountability. But ultimately, if there needs to be a change that affects the entire organization, it’s the CEO who makes the decision on the scope of the process, the points of interface, and resolves the issues that cannot be resolved lower.

The Basis for Cross Functional Accountability and Authority Work

It therefore becomes imperative for cross functional work to identify the manager that is the Effective Point of Accountability® (EPA) for the work. The easiest way to identify this person is to think about who has the authority to Decide and Direct, in other words, to decide what will be done and to direct each person involved to comply.

- Approve policy, process or standard as recommended by delegated direct report.

- Set Context and Boundaries for all involved direct report managers

- Resolve issues that cannot be resolved by direct report managers

- Reset context based on issues resolution.

This work is inherent in authority as a manager of direct reports. The Manager with the Effective Point of Accountability® has, inherent in their position, the authority to decide and direct work within their area of authority.

Policy, processes and standards provide the basis for a most cross functional work, as these codify the way in which work is done. They become part of the organizational context for doing work. This is also part of the managerial accountability and authority framework. For example, the CEO might hold the CHRO accountable for developing, maintaining and approving the human resources policies processes and standards in the organization. This does not mean that the CHRO has the authority to establish the human resources policies processes and standards – as they are organization-wide the CEO must approve them. The CHRO would recommend them after appropriate consultation. And the CHRO would in most cases be delegated the accountability and authority to monitor adherence.

The EPA must delegate the accountability for appropriately consulting, developing, and then recommending the policy, process or standard. That individual then has the authority to:

- As delegated, recommend policy, process or standard to the EPA in collaboration with involved peers.

- Recommend changes to the EPA in collaboration with involved peers.

Once the policies processes and standards are in place, they form part of the context for how work is done within the organization.

But this is only the starting point, or the base line, for cross functional work. There are three types of accountability and authority relationships that exist and each of these has two sub categories. If you’d like to learn more about these, watch for future articles, or check out the related Webinar on the Effective Managers(TM) YouTube channel: Accountability 101: What You Need to Know about Accountability in Your Workplace.

To learn more about how these concepts can apply in your situation please contact me or view our recorded Webinar:

See the Webinar on our YouTube Channel

This Webinar includes 60 minutes of helpful content and a review of the cross functional accountability and authority relationships in organizations.

Email me for a pdf of the slides – free to managers and HR departments in organizations.

And don’t forget to subscribe to the Effective ManagersTM YouTube channel to receive notices of new content.